“HONESTY AND OPENNESS IS ALWAYS

THE

FOUNDATION OF INSIGHTFUL DIALOGUE.”

BELL HOOKS, ALL ABOUT LOVE: NEW VISIONS

WELCOME

This quote is from Malika, an employee of a DSAA member company. For Malika, things are working well: her workplace feels comfortable and she told us that most of her colleagues understand what building inclusive working cultures is about.

ABOUT

From our interview with Malika as well as many other conversations, we know that while belonging to an underrepresented group in any environment can be tricky, it is possible to design inclusive working environments. In the process of creating such working cultures, the help of every single employee is needed. Everyone can make a difference and everyone is mutually responsible for making this work. Whether in your specific working situation your accounts would be similar to those of Malika, or whether your company is not at all as advanced, there are plenty of practical things you can do to become a driver of change.

On top of the fact that such a working environment makes work more enjoyable for everyone involved, it is good for business too. Research shows that diverse teams achieve better results and produce more creative ideas. This means that your own potential is unlocked differently if you are placed in a diverse team, consisting of individuals with different identities.

The handbook consists of three main parts: in the first step you will learn about the current situation regarding gender equity and inclusion. We want to help you to recognize the underlying structures that lead to the inequality of women and people with disabilities. The handbook also offers information about various forms of bias, how they operate and what that has to do with inclusion. You will see various examples of how discrimination can (sometimes very subtly) manifest in the workplace. Lastly, we will guide you to reflect your own beliefs and biases and provide you with some helpful checklists and exercises to learn how to cope with bias and better include women and people with disabilities in the future.

Consider this handbook a toolbox that you can make your own. You might work within the BPO sector in Ghana, you might be situated in software engineering in Rwanda. To quote one member of the DSAA network: “a toolbox is a toolbox. Not everything has to work for everyone - everyone can pick whatever they need.” This handbook is meant to serve as a source of knowledge that you can refer back to again and again. It provides you with concepts and mindful language to talk about your own experiences and address discrimination in the workplace.

We would like to thank you for your interest in joining us on this journey. We hope it helps you bring this knowledge to your workplace and act as a driver of change. If you have any further questions, please feel free to contact us at any time.

IN-VISIBLE and the DSAA team

FRAMING THE PROBLEM

In many places, women and – even more so – people with disabilities (PwD) do not have the same access to employment that men or people without disabilities have. While laws are in place that technically guarantee equal rights, including the right to work, these usually do not translate to truly equal opportunities.

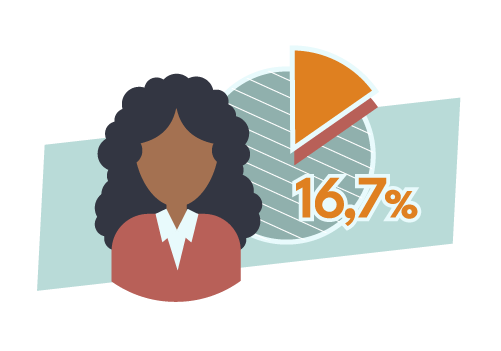

For example, in Morocco, the female employment rate was just 16,7% in 2020 (Statista, 2021), and while the employment rates of PwD are not frequently published, older reports suggest that they are similarly below those of people without disabilities – for example, in 2013/14 only around 52% of people with disabilities in Rwanda were employed, compared to 71% of the general population (Development Pathways, 2019). And for women with disabilities, the rates can be even lower. Why is that so?

In the case of women, a lot of the time they are expected to marry at a young age and spend their lives caring for their husband and children, rather than enjoying higher education and a long-term career (Abbott & Malunda 2016). Women that are employed outside the home experience the extra strain of having to continue working for their family after getting home from working for their employer.

Take Ghana, for example: according to a 2020 UN Women report Ghanaian women spend around 14,4% of their time doing household chores, while it’s only 3,5% for men (UN Women, 2022). Even women in leadership positions who are their household’s main income earner report having to do the majority of chores after returning from a stressful workday (Mumporeze & Nduhura, 2019). Coping with this inequality is just one part of the picture that causes a burden for women. Going into other hardships that women are disproportionally affected by, such as sexual harassment, sexual assault and domestic violence, all of which remain all too common worldwide, would go beyond this handbook.

For example, according to a 2021 report only 40% of PwD in Senegal even attend primary school, significantly less than average (United States Department of State, 2021). PwD’s access to the workforce is further limited by spaces and technology being inaccessible to them, for example when information is only available in print format, excluding blind people and those with visual impairments. Some countries in theory require public transport and buildings to be accessible, but that isn’t always executed in practice (Ocran, 2019) and does not necessarily apply to private properties, such as offices.

Efforts have been made to address these inequalities. Each of the countries that DSAA member companies reside in has some form of law addressing equal rights, as well as programs such as Egypt’s recent “Gender Gap Accelerator”, aimed at supporting women in the workplace. In many countries, PwD are legally entitled to certain support measures, for example financial assistance. NGOs and other organisations are working to improve the living situations and employment chances of women and PwD. And yet, things are changing slowly: laws are not always applied, people are left out because of a lack of knowledge or resources (e.g. in rural areas), and, perhaps most importantly, people may not understand why change is needed at all.

CLARIFICATION OF GENDER & INCLUSION CONCEPTS

First things first: Diversity essentially means variety. A diverse team ensures the presence or representation of all kinds of different identities, regarding traits such as gender, race, migration experience, age, disability, social class or many others. This doesn’t mean simply checking off a list of superficial traits, but to create a space for a variety of experiences and needs, and to make use of their points of view. For example: if we talk about gender diversity, this then means ensuring that people of all genders, and not just men, are represented and get their voice heard. This is in contrast to the status quo all over the world, where most positions of power are held by men and thus women are significantly less represented and taken less seriously.

SUMMARY

Summarising, what we have covered so far. Enhancing gender diversity and inclusion are at the forefront of DSAA’s member and partner companies, but also within the wider business community. Some main take-aways regarding the terminology

01

G&I stands for Gender and Inclusion.

At the workplace, G&I has the aim to represent women and PwD at all levels as well as to assure they can participate and get their perspectives in.

02

The structural and historically engrained discrimination of women is referred to as sexism.

03

The structural and historically engrained discrimination of people with disabilities is called ableism.

INCLUSIVE WORKSPACES

“Provide training on sexual [harassment] and define clear cut policies on [how] to report it alongside [aid] provided to victims.”

“Hire more people with disabilities and get infrastructure that would allow them to feel free”

“It would be great when [company name] moves to a completely Inclusive facility. Although, it is trying really hard to make our current office spaces disability friendly as we do not own the properties we occupy.”

“People with disabilities should be given the opportunity to participate in overall aspect.”

“There has been attempts in the past to educate members about living with people with disability. I feel more such educational programs can be of great help to all employees”

“Special facilities should be made available for them to ease their activities”

“Hire more people with disabilities and get infrastructure that would allow them to feel free”

While the IT industry holds a lot of potential for PwD, providing jobs that don’t necessarily require physical presence, the overall mind-set of the company remains an obstacle. One interviewee put it this way:

“Today, many hurdles are a little bit smaller. To get the right education is easier, to pursue your secondary school courses and exams is an option - online. And you can even be recruited and stay at home.”

Similarly, while the BPO sector already has a large presence of women and would seemingly be one where female careers could be advanced easily, “you have to pass the message that gender equity is necessary to reach gender equality”, an employee says.

(UNCONSCIOUS) BIAS

But why is it so difficult for us humans to treat everyone the same? According to cognitive research, our brain – particularly our decision making process – is actually rather easy to manipulate. In 2011, the Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahnemann published the book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” (Kahnemann, 2011), in which he compiled the main findings of his research. He describes the different ways our brain systems function and how these make us susceptible to cognitive biases. What does that mean?

One of the key learnings from Kahnemann and others’ research is that all of our decisions, opinions, and actions are based on “unconscious rules of thumb.” These unconscious rules are a kind of shortcut that our brains remember based on past decisions, social codes, and cues. They underlie our intuition and are responsible for the fact that making bad decisions is sometimes unavoidable. Results of psychological experiments show that, for example, statistical data and logic are massively neglected in decision making and that our brain cannot be influenced by rational arguments when a “feeling” has already set in (Benedetto et al., 2006).

Many ask themselves: How can it be that so many people give more credence to a perceived truth than to scientific facts? And this question is also highly relevant for decisions at the workplace, because studies show that women, for example, are often perceived as less competent than men, even if they have the same qualifications. The “facts” – in this case their CV and skillset – speak in their favour, yet the decision is made against them (Begeny et al., 2000 and Moss-Racusin et al., 2012).

Why do people fail to make fair decisions? A simple answer to the question is: Because our brains cannot actively process the huge masses of information that hit us every second. Information overload. So, on the one hand, large parts are filtered out, i.e. not “perceived” at all. On the other hand, in order to make the complexity of our world more easy to process, we tend to think in categories that simplify reality – but because they have developed over such a long time, we often don’t see that they don’t contain the whole truth.

In many situations this filtering process is helpful. We would be unable to navigate in a world in which several million units of information have to be consciously weighed every second. Often, quick perception and unconscious reaction patterns even save our lives: If we are walking to work as pedestrians, half asleep, and suddenly hear a car honking behind us, we immediately jump to the side and are alarmed. We don’t have to sort out arguments in our head to decide what an appropriate reaction would be. Instead, we use a kind of shortcut that the brain has memorised because it has worked well so far.

However, when it comes to the impact of our brain shortcuts on workplace decisions and corporate culture, they may be less helpful. Gender and the expectations and social norms attached to gender roles play a major role here, leading to phenomena such as gender bias.

GENDER-BASED DISCRIMINATION

While denying a person a job on the grounds that she is less suitable “as a woman” is not legally acceptable (anymore), our human brain is not as progressive all the time. As we have seen, all perceptions and decisions we make are far from being “neutral”. Research shows that the long tradition of formal and social inequality of women is still embedded in our thinking today – and it generates various kinds of bias. Among them is the gender bias.

You may have stumbled across the word bias in various contexts: a bias describes effects in data sets, calculations, perception, and thinking. In statistics, a bias is a systematic error that potentially has a distorting effect on the overall data collection. There are also biases that seem to be programmed into the way we think: so-called cognitive biases. For example, when we make a decision, we tend to give more weight to the first piece of information that reaches us rather than to subsequent pieces of information. This so-called anchor effect (Tversky & Kahnemann, 1974) is often used in advertising: A product is labelled with two prices, the supposed original price – now crossed out – and the supposed reduced price. Regardless of how much the product is worth or whether a reduction has occurred, we think we are landing a bargain (HubSpot, n.d.).

Other biases are socialised and grow out of social structures. We are often influenced, usually without realising it, by sexist, ableist or other prejudices; the list goes on. Thus, our perceptions, the choices we make, and judgments we make are skewed. In the case of gender bias (Eichler et al., 2000), as the name implies, it is a bias, a skewed judgement, based on gender (3). Similar to a small error at the beginning of a mathematical calculation, gender bias distorts everything that follows. It’s a kind of learned, sexist thinking error.

The term gender bias originated in relation to conditions in scientific research, but it also affects and shapes our everyday lives. This is also the case at work. Since the 1970s, there has been a steadily growing body of research on bias in work culture that addresses the phenomenon across countries and industries.

Gender biases feed on existing structures, are taught to us and further reinforce inequalities. Unequal division of labour and unpaid reproductive work further burden women. Opportunities in the labour market are also shaped by bias, as evidenced by the so-called gender pay gap and unbalanced gender ratios, especially at the executive level.

GENDER BIAS 1:

ANDROCENTRISM

GENDER BIAS 2:

GENDER INSENSITIVITY

GENDER BIAS 3:

DOUBLE STANDARD OF EVALUATION

BIAS AT THE DSAA

Gender bias is relevant in any workplace, also within the DSAA member companies. Here are some examples of employees about gender bias.

01

02

03

“Women have childcare duties and their social environment is going to be sceptical of their job. This is an extra burden and they need advocates at companies that put in a word for their needs.”

As described, gender biases are a structural problem that cannot be combated only on a personal, interpersonal level. It is also up to companies to critically examine their own work culture and initiate change. Changes can thus run through the institutional level to the confrontation with personal beliefs. Behind every organisation are people. And their decisions have an impact, whether it’s evaluating employees, setting up new structures, or driving specific changes. People who are sensitive to gender bias and corresponding impacts can work proactively to address it. Remind each other, anticipate, question. After all, if you don’t see the problem, you become part of it. It is important to acknowledge that bias cannot be “trained away.”

All people have biases – so it is important to bring them out of the subconscious and into consciousness. This is where forming diverse teams can help; after all, people learn different codes and correspondingly different biases depending on culture and context. Encouraging different perspectives in the team and giving everyone enough space to ask critical questions is therefore an important first step in making the invisible visible. It can help to get support “from the outside.” In a workshop on the topic of gender bias, participants learn the necessary tools to uncover invisible biases and to work together on the work culture.

To build gender inclusive work cultures, we must thus first understand our gender bias. Or, put differently, we can ask ourselves: how does gender matter to me when I meet a new person or collaborate with my colleague? From there on, we can begin to explore what gender exclusion mechanisms look like.

EXERCISE

CASES

These are some typical examples of gender inequality or gender-based discrimination.You can either read the cases by yourself and self-reflect. Alternatively, you may ask one or two colleagues or your team to join you on a little discussion round about these cases. Proceed as follows:

2 MINUTES

5 MINUTES

5 MINUTES

5 MINUTES

One person reads out the case.

Everyone writes down immediate reactions and feelings.

Everyone shares their notes in a row.

Open discussion.

This case is one example of the ways that women are expected to be responsible for care work, not just in their families, but also in the workplace: even though the woman who reported this is a participant of the meetings just the same as her male colleagues, they assume that she will do all the small tasks that are necessary for a meeting to go smoothly. This is a very common occurrence in the workplace: women are often made responsible for things such as preparing team lunches, organising work events, arranging rooms, making bookings, and much more. That means that they have less time to concentrate on their work tasks, while their male colleagues reap the benefits – often without realising that this unseen work makes their days go much more smoothly. This in turn may make female employees feel frustrated and underappreciated, leading to lower job satisfaction.

We mentioned double standards before, and this is a great example. Men certainly lean on tables and cross their legs while speaking, too – but when they do it, it’s at worst considered relaxed or informal, but certainly not insecure. But this case also shows two more issues: women being judged by their appearance and men offering unasked-for and often unneeded advice. We can ask ourselves: is the position of her body really relevant to what she was saying? If her presentation is insightful, why does it matter how her legs are aligned? The same is true for men, of course, but women in particular are often expected to not just be competent, but also, to put it bluntly, decorative. This ties in with the unneeded advice: men often believe women to be less educated, aware and competent, therefore feeling the need to explain things that the woman might very well already know.

“During a meeting (I’m the only woman) I was asked for my opinion on the topic. Before I could say anything, a colleague said “Before you say your nice closing words, Mrs. ABC, I’ve got another contribution to the topic.”

Many studies have been conducted on speaking times and interruptions in meetings, and the overwhelming majority of them show: women get less time to speak and are interrupted much more often than men. And not just that, men also tend to believe that speaking times were equal when in reality women spoke much less, and that women were speaking more often than men when in reality speaking times were equal. So for a man to take the word after a woman was asked for her opinion is unfortunately quite common. In this case, we also need to pay attention to how the interruption is phrased: even though the woman was asked for her opinion on the topic, her male colleague calls it her “nice closing words”, implying that they’re inconsequential in comparison to his “contribution to the topic”. Just as in case number 2, even though the woman is his equal colleague, she is taken less seriously and reduced to the supporting role of making the meeting “nice”.

DISABILITY-BASED DISCRIMINATION

Just like gender based discrimination, discriminating against people with disabilities does not require a bad intention. Most people act discriminatory accidently, because they are not aware of the patterns and narratives that they were told about people with disabilities, let alone their implications. As put forward in the definition of disability, the norm that our society operates on is one that assumes individuals are able-bodied. Hence we all learn, growing up, that a standard human is not disabled but instead in a condition that allows them to do anything they want to. Of course this is not true, and not only for people with disabilities but also for many other groups based on their individual physical or mental condition. However, the social narrative is so strong that it persists despite the examples that would counteract this (e.g. elderly who cannot use their bodies in any desired way anymore). Similarly to gender, where the norm is rather male than female, and the female is always the “other”, the derivation of this norm, ability is also portrayed as the “right” way.

As a result, we discriminate. Not because we want to but because we have internalised this perspective as “normal”. “Normal” is a tricky word. What is normal? Who is normal? In our societies, this word is characterised by a male person who has no impairment whatsoever. Conversely, this means that everyone else falls at least somewhat outside of this norm. This is evident not only in our schools, businesses, institutions, but even in our technologies.

Discrimination against people with disabilities can take many forms. On a bigger scale, there is often a lack of accessibility, meaning that spaces or information are not designed in such a way that PwD can use them. For example, if a company uses software that does not allow the use of screen readers, blind employees might not be able to use it. If someone is deaf, they may need information in a written format instead of in a phone call. On a societal level, many people still hold a lot of prejudice about people with disabilities, maybe even believing that disabilities are a punishment by god or caused by supernatural forces, and treat PwD with suspicion and fear (Mfoafo-M’Carthy et al., 2020). Children with disabilities may be kept away from the public out of shame or forced to beg, depriving them of education and career prospects (UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2019). And when it comes to personal interactions, PwD often experience being looked down upon and not taken seriously, people talking to their caregiver instead of them as well as the use of degrading language.

EXERCISE

CASES

These are some typical examples of discrimination that people with disabilities experience.

You can either read the cases by yourself and self-reflect. Alternatively, you may ask one or two colleagues or your team to join you on a little discussion round about these cases. Proceed as follows:

2 MINUTES

5 MINUTES

5 MINUTES

5 MINUTES

One person reads out the case.

Everyone writes down immediate reactions and feelings.

Everyone shares their notes in a row.

Open discussion.

“I am hard of hearing and whenever I applied for a job, people would tell me “your credentials are great, but we just wouldn’t know how to communicate with you” or something like that. Even when it’s a job where I would mostly work on my own, they’re not even trying to accommodate me.”

Physical access can be a big problem for people with some disabilities. This includes things such as buildings without elevators (which can be an issue for people using wheelchairs, amongst others) and software that is not usable by blind people, but also companies and colleagues being unwilling to even try to accommodate the needs of the PwD. Some of this depends on factors outside of the control of a company, such as accessible public transport to the workplace. But many other accommodations can be made if everyone is willing, including making an effort to learn how to communicate with deaf employees or providing assisting tools such as screen readers for blind employees. Simply refusing to hire people with disabilities out of an unwillingness to learn can be a barrier that is quite unnecessary and you can easily contribute to the inclusion of people with disabilities simply by making an effort to engage with them.

“People seem to think that just because I can’t read well, I’m stupid. This one colleague always complains that my emails to him have too many mistakes and he has such a hard time understanding what I’m trying to say. Sometimes I wonder if I’m really good at my job or if everyone secretly thinks I’m a burden.”

People with cognitive disabilities, such as lower reading and writing abilities, often find that their intelligence is judged by certain skills that are not really an indication of how much they know or what they can do. Someone with a cognitive disability might be an expert in their field, while someone else may have excellent writing or speaking skills but little else. Including people with disabilities better can be as simple as recognising where certain skills are needed and where not. In this case, an internal email to a co-worker doesn’t need to be perfectly phrased, and if the co-worker doesn’t understand something, he can easily ask for clarification. If it was an email to a client, a simple solution would be to have a co-worker proofread it. Unfortunately, it’s common to expect PwD to accommodate people without disabilities instead of the other way around – such as a co-worker, who is concentrating on how someone else’s disability is inconveniencing him, rather than acknowledging how social expectations exclude people with disabilities.

“All the time my co-workers tell me “XYZ, why do you take so many breaks? Can’t you work faster? Why are you always running around?” I always get my work done on time, but I’ve got a chronic pain condition and sitting for a long time can be hard sometimes. But I don’t want to say anything, because I’m afraid they’ll think I can’t do my job.”

This case shows the common assumption that all disabilities are immediately visible, which can cause a lot of problems for people with invisible disabilities – even though they are very common and may include a wide range of cognitive disabilities, chronic illnesses, mental health conditions and so on. By focusing on visible disabilities and assuming that everyone else has the same physical and mental capabilities, the needs of people with invisible disabilities are often ignored, even more so if they’re young and look “fit”.

When asking for accommodations, people with invisible disabilities are frequently not taken seriously or even accused of lying about their condition, causing shame and leading to many hiding their disabilities at work. When they do accommodate their needs, others might accuse them of laziness or slowness. This causes psychological stress and may affect their work performance in the long run, as they continuously ignore their own boundaries in order not to stand out from their non-disabled colleagues. It can be helpful to focus more on the results – i.e. is the job getting done and done well? – rather than someone’s working style.

SOLUTION SPACE

Every employee of every company has their part in co-creating the working culture. While you’ll depend on management to implement some larger measures, an inclusive workplace also needs employees who are willing to learn and grow together.

DO’s

So what can you, personally, do in order to help women and people with disabilities feel more included and comfortable in your workplace? Here are some suggestions:

DON’Ts

Here are some things you should avoid doing or saying:SUMMARY

Now, you may agree that this check-list sounds fair, but you are wondering how to do this. Indeed, many of the don’ts from our list are common practice and thus effectively not easy to avoid doing. Similarly, the do’s are not always aligned with how we learn to behave or act towards others – as we have internalised somewhat sexist and ableist attitudes. Following, we thus present to you things that will help you to reflect your attitude, become more self-reflective and communicate about your observations in a constructive manner:

Do mindfulness exercises to test yourself.

Next time you board a bus, listen to a presentation, are impressed by someone: take a minute and ask yourself why. Why do I sit next to this person on the bus, why does this other person make me uncomfortable? How would I perceive this presentation if it was executed by someone who had a different age, gender, physical appearance? Why do I feel impressed? Which cue about this person leads to this emotion and what does this say about me?Be patient with yourself.

Changing thought processes is not something that is done easily, nor quickly. Take your time to unlearn and use tools that make progress visible. Journaling about this topic once a week would be a great way to start. Alternatively, you could also find a few colleagues and agree on regular check-in meetings. These don’t have to be very frequent, regularity is key here.Advance your communication.

Once you challenge your own assumptions and advance in your unlearning journey, you will see things you didn't see before. Communicating about these observations can be tricky, because you don’t want to offend anyone. It can help to split the observation and the interpretation into two separate parts. The observation is objective, that’s something you could also see if you had filmed the interaction (e.g. I observed that you interrupted Malika for the third time; I observed that you were 10 minutes late the last three meetings). The interpretation part is where your personal interpretation and your needs come into the conversation (e.g. I would like to foster a speaking culture where everyone can contribute; I would like to assure that our meetings can start on time). You can also add a wish and ask a specific request from your colleague, without being rude. The key here is empathy: By splitting the interpretation from the observation, you assure that all parties involved have a shared understanding of what happened. The why and how and whether that’s a problem can then be discussed from this place of mutual understanding.We have almost reached the end of this handbook. To manifest your learnings, we encourage you to go back to the contents of this handbook whenever you feel insecure or want to deepen your understanding. Moreover, to give you the chance to revise and to test yourself, we would like to close this handbook with some final exercises.

TIP

Of course, you can do all of these exercises either by yourself, or in your team. Get creative and play around with the prompts and make them work for your specific environment.QUIZ

Time's up

Time's up

Time's up

EXERCISE

TRAFFIC LIGHT

After reading this handbook, please take a moment to reflect on what you learned and how you would like to move forwardcases. Proceed as follows:

01 SETTING UP

02 REFLECT

03 SHARE (OPTIONAL)

Stay in Touch

We hope the toolkit has helped you to get acquainted with G&I and perhaps also empowered you to carry what you‘ve learned into your organisation. We are looking forward to hearing from you with any remaining questions or remarks. You can reach out via our social media accounts on Instagram and LinkedIn and we will be happy to get in touch with you.

For now, we would like to thank you for taking the time to learn and to unlearn, to self-reflect and to become a driver for change within the DSAA community.

The IN-VISIBLE team